FF-7 Spanish Riding School Text

The Spanish Riding School

For four centuries, the Spanish Riding School has brought equestrian glory to Vienna.

For four centuries, the Spanish Riding School has brought equestrian glory to Vienna.

People from all over the world come to watch the thrilling performances of the white

horses and their colorfully dressed riders. The stallions and their riders are the last

remains of the classical school of riding. They perform the same classical exercises

practiced by the Greeks many centuries ago, and their motions are as beautiful as

a dance.

The school is located in Vienna, Austria, and it dates back to 1565.

In 1735, it was named "The Spanish Riding School of Vienna." The term "Spanish"

has nothing to do with a "Spanish" way of riding, or with any riding school in Spain.

It simply reflects the Spanish ancestry of the horses at the school.

The horses at the Spanish Riding School are called Lipizzaners. They are known

for their beauty, grace, spirit, and gentleness. Most Lipizzaner horses are born with

dark coats. But, as the horses grow older, the coat turns lighter until it becomes a

handsome milk white. Now and then, a brown or black stallion is produced. There is

an old saying that bad luck comes to Austria whenever there is no dark stallion among

the Lipizzaners.

For example, in 1809, Napoleon entered Austria; in 1934, a hated government

was set up in the country; in 1938, the Nazis overran Austria. These were all years

during which there was no dark stallion. Of course, the color of a horse could not

determine the fortune of a country. Still, the dark stallions are well cared for!

The valuable Lipizzaners are raised in such a way that they do not know the meaning

of fear. They are taught with kindness, firmness, and gentle understanding. At the

school, the saying, "Never let a horse stop with a sense of defeat," is taken very

seriously. Toward the end of a lesson, if a horse | has not performed well, the trainer

will have him perform an easy exercise. The horse leaves the ring knowing he has done

a good job, and the next morning he will come to back to the ring with fresh eagerness.

The young stallion does not enter the school until he is nearly four and will not be

fully trained until he is eight. At the age of two, when a racehorse is at his peak at the

track, the Lipizzaner is spending long carefree days grazing in meadows. At twenty-five,

when the racehorse has long since been put out to pasture, the Lipizzaner may still be

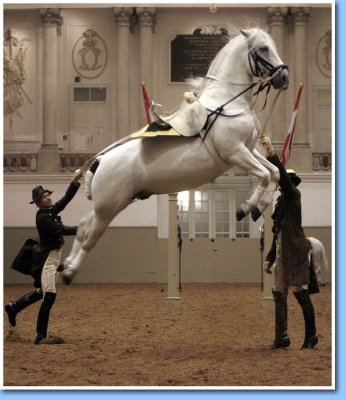

a star performer at the riding school. The Lipizzaners are trained for forty-five minutes

a day. Their exercises range from trotting in place, to wonderful leaps into the air.

Their legs act like strong springs and their bodies seem to float effortlessly through

the air. The Lipizzaner and his rider seem to move as one being. Together they are

equestrian perfection.

The system of teaching at the riding school works two ways. The old horses teach

the new riders and the experienced riders educate the young stallions. A well-schooled

Lipizzaner can provide a valuable learning experience for an inexperienced rider — but

he can, and sometimes does, make a fool of his rider. Many stories are told about

pupils who are so sure of themselves that they forget the part their horse plays. They

sometimes take all the credit for a perfect performance — only to find themselves thrown

onto the sand by an unexpected leap or turn!

During the closing days of World War II, the school was seriously threatened. The

Red Army was in a position to capture and destroy Vienna. Colonel Podhajsky, the head of

the Spanish Riding School, realized the danger. If anything should happen to his horses,

the thin tie with the classical riding of the past would be broken forever. The Colonel was

able secretly to move many of his stallions out of the city to upper Austria before the

bombing began. When the bombing of Vienna started, only the Colonel, two brave riders,

and ten stallions were left in danger.

The bombs and gunfire were frightening, but the horses behaved magnificently. When

the air-raid signal sounded, the horses would file out of their stalls without even being called,

ready to take shelter in the passageway of the riding hall. Bombs often exploded nearby,

and broken glass showered the horses and the three men. The Lipizzaners would

crouch down almost flat against the ground and wait until the attack was over.

Colonel Podhajsky said, 'They may have shivered, but they never panicked."

However, Colonel Podhajsky knew he had to get his horses out of the city. He managed

the almost impossible task of getting railroad cars for his horses. Soon, the white

horses were safe.

But, for ten years after the war ended, the Lipizzaners wandered in the Austrian

meadows. They could not return to their school in Vienna because of the bomb damage and

lack of repairs. Finally, in 1955, the magnificent Lipizzaners were brought home.

"It was the greatest moment of my life," the Colonel admitted. "When I had left the school

in 1945, with Vienna coming down around my ears, I had thought I would never see it again.

Yet here we were, putting on a great performance for members of the government, for

parliament, for everyone — and do you know, it was exactly 220 years since the opening of

the riding hall! I wrote the dates into the sand of the ring for all to see: 1735-1955."